The History of Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) in the United States

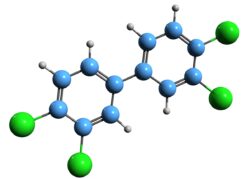

Polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, represent one of the most significant environmental and regulatory challenges in modern American history. Originally hailed for their remarkable industrial utility, PCBs were later recognized as a major public health and ecological hazard, leading to their eventual ban. The story of PCBs in the United States is one of innovation, unintended consequences, and regulatory evolution.

Discovery and Commercial Use

PCBs were first synthesized in 1881, but large-scale commercial production did not begin until 1929, when the Monsanto Chemical Company (later known as Monsanto Company, now part of Bayer) began manufacturing them under the trade name Aroclor. Engineers and manufacturers quickly adopted PCBs because of their unique chemical properties: they are non-flammable, chemically stable, resistant to heat, and excellent electrical insulators.

These traits made PCBs indispensable in a wide range of products, including:

- Electrical equipment such as transformers and capacitors

- Hydraulic fluids and lubricants

- Carbonless copy paper

- Plasticizers, adhesives, and sealants

- Paints and coatings

By the 1960s, PCBs had become a cornerstone of U.S. industrial development, with hundreds of thousands of tons produced.

Rising Concerns and Early Warnings

While PCBs were celebrated for their utility, concerns about their safety emerged as early as the 1930s, when industrial workers exposed to PCBs reported cases of chloracne, liver damage, and other health issues. Research in the 1960s revealed that PCBs do not easily break down in the environment. Instead, they persist and accumulate in soils, sediments, and living organisms, especially in fatty tissues.

In 1966, Swedish scientist Sören Jensen detected PCBs in wildlife samples, marking one of the earliest indications of their widespread environmental contamination. Studies in the United States soon confirmed that PCBs were present in fish, birds, and human tissues, raising alarms about long-term exposure and potential health risks, including cancer, reproductive harm, and immune system suppression.

Regulation and the 1979 Ban

Mounting evidence of environmental and health hazards led to increased scrutiny in the United States during the 1970s. Public concern intensified after reports of contaminated waterways, particularly the Hudson River in New York, where General Electric had discharged large amounts of PCBs over decades.

The turning point came with the passage of the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) of 1976, which gave the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) authority to regulate the manufacture, processing, and distribution of hazardous chemicals. Under TSCA, the EPA moved to phase out PCBs, culminating in the 1979 ban on PCB production and most uses. Certain limited, enclosed uses, such as in transformers already in service, were allowed to continue under strict regulation.

Timeline of Major PCB Events in the U.S.

- 1881 – First synthesis of PCBs.

- 1929 – Monsanto begins commercial production under the trade name Aroclor.

- 1930s – Reports of worker health issues, including chloracne and liver damage.

- 1966 – Sören Jensen identifies PCBs in the environment, triggering global concern.

- Late 1960s – PCBs detected in U.S. fish and wildlife; studies link them to bioaccumulation.

- 1970 – EPA is established; PCBs become a focus of emerging environmental regulation.

- 1972 – U.S. bans PCBs in open-use applications such as adhesives and paints.

- 1976 – Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) enacted, giving EPA authority to regulate PCBs.

- 1979 – EPA bans production of PCBs and restricts their use.

- 1980s–1990s – Major Superfund cleanups initiated at PCB-contaminated sites nationwide.

- 2000s – Large-scale dredging and remediation projects begin in the Hudson River and other waterways.

- Present – PCBs remain a priority pollutant under EPA monitoring and cleanup programs.

Legacy and Ongoing Issues

Despite the ban, PCBs remain a persistent environmental problem due to their chemical stability. Large quantities of PCBs are still present in soils, sediments, old equipment, and building materials. Major cleanup efforts have been undertaken at sites such as the Hudson River, the Fox River in Wisconsin, and numerous Superfund locations nationwide.

PCBs continue to be detected in fish, wildlife, and even human populations. Because they bioaccumulate and biomagnify, they remain a concern for communities reliant on subsistence fishing, particularly in the Great Lakes and along contaminated river systems.

Conclusion

The history of PCBs in the United States illustrates both the benefits and dangers of industrial chemistry. Initially a technological triumph, PCBs became a symbol of the unintended consequences of synthetic chemical production. The American response—from widespread industrial use to eventual prohibition—shaped modern environmental policy and underscored the importance of precaution in chemical management.

Today, while PCBs are no longer produced, their legacy endures in ecosystems, communities, and regulatory frameworks, serving as a cautionary tale of balancing innovation with long-term environmental stewardship.